You may love this guy, but you’re not supposed to. In fact this is the picture that tells you you’re being had.

Before he was the beloved sheriff of Mayberry – beloved by some; the show never did much for me, alas – Andy Griffith was a comedian known for down-home country humor records. He did Ed Sullivan, did some Broadway, then made a film debut in “A Face in the Crowd,” the 1957 movie that’s the subject of today’s weekly Noir. (Okay, it’s not noir. Not at all. Not in the least. This feature will eventually become “the weekly old movie I watched on my computer Friday night while doing the next week’s Bleat graphics.”) The title makes it sound like some sort of grim “relevant” study in Modern Alienation, but as the picture above shows you, grim and alienated it wasn’t. What we have here is a guy who took all the good will and familiarity he’d built up thus far and dynamites it for the sake of making a damn good movie, and that’s rather brave: picture Bob Newhart playing a psycho sex killer in a ’66 crime drama – then picture Bob Newhart returning to his previous button-down persona without missing a beat, and going on to decades of success. That’s what Griffith did.

The movie concerns a fellow discovered in an Arkansas drunk tank by a small-town radio producer (Patricia O’Neill) looking for local color. One of those WPA-style discover-the-real-America things. She wakes up a surly inmate sleeping with a tattered suitcase and a battered guitar; he calls himself Rhodes, and she names him “Lonesome Rhodes” on the spot. He plays a tune. He has a certain something – not Elvis-class something, no. It’s raw and mad and happy and whatever it is, it does not care about anyone or anything. She tapes his song. She convinces her station to let him have an hour in the morning. Naturally, he’s a hit, and we can see why – he eats on the air, tells jokes, bangs an E chord to make his points, flatters the housewives, and has genial contempt for the medium. If the movie had simply been about Lonesome and this town, it might have been a nice little period piece with lovable rogues and proto-Mayberry folk, but the creators – Kazan, director, and Schulberg, writer – have great pretensions. Rhodes is a new archetype, a natural force who understands the power of the mass medium with an unnerving directness that cuts through the intermediary distances and artifices, and makes him one of the most powerful men in America. (He ends up advising a presidential candidate before the movie’s through.) As drama, it works; as social commentary, it’s a bit dated, but only because it was one of the first to really hammer home these points about mass culture, advertising, TV, etc. It’s almost 50 years old, and still seems fresh – partly because the audacity of the middle of the movie, when Lonesome puts his stamp on advertising culture, still crackles. This was, in its own way, quite subversive.

But not that subversive. Madison Avenue and advertising were already the subject of lampoons and parodies, so taking on consumer culture didn’t guarantee a shift in the Gulag. But still: if if these sacred oxen had been gored before, this was a thick sharp spear shoved in with gusto. And just clever enough to avoid tipping into silly hyperbole. Almost. The picture at the top of the page is from an amusing montage of an ad campaign for a worthless vitamin supplement, which Lonesome Rhodes has managed to make into some sort of proto-Viagra.

The print is lovely, and the movie’s a delight to look at. Mostly. Let’s get to the screen grabs, no? Here we have that wonderful rarity, the egregious big-studio boom shot!

Here’s our hero, as we see him at first – able to go sullen and dark in a second. Few today think of Andy staring over beer bottles, half in the bag, full of resentment. But in a way this was a natural extension of his happy-hick persona – just added another side.

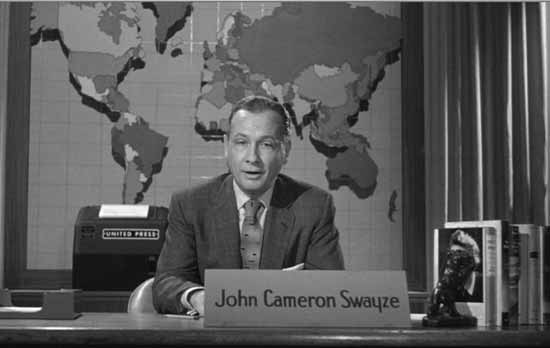

The movie calibrates Lonesome’s rise to media prominence by calling in real live media figures, the same way the dessicated husk of Larry King is pressed into service in modern films. Thus the film serves as a nice who’s who for 1957. Here’s a fellow people from my age demographic recall solely from Timex commercials, John Cameron Swayze, king of a planet where the oceans have drained to give the continents that nice drop-shadow look.

After Lonesome goes big time and moves to New York to do a TV show, he gets a writer – Walter Matthau, of all people – and there’s a scene in a bar ‘twixt Walter and Patricia O’Neill, who has followed Lonesome on his ascendance because, of course, she loves him. In this bar we have a rather remarkable collection of background characters:

Burl Ives and Bennett Cerf. It’s interesting to see Burl Ives show up, since Kazan was reviled for naming names before HUAC, and Burl was one of those fellows across whose name a red shadow fell.

As with most films we highlight here, you have old stars at the end of their tenure and new up & comers. Lonesome goes back down south for a PR tour, and the camera pans across a line of baton-twirling cheerleaders. One leaps out right away, before the camera lingers on her. Then she gets a close-up.

It’s Lee Remick. Looking on in the stands, framed by the obligatory clichéd Southerners – old tired man and fat sexless matron – we have the thinking man’s Tony Curtis, Anthony Franciosa!

And in the theater where Lonesome makes his TV debut, we have this guy!

You know, this guy!

Oh, come on. You know who that is. No? And I suppose you don’t know who this is, either.

That’s right: it’s a news interview with that famous newsman, Mike Wallace. One of the undead, it would seem. And this one?

The Linda Kelsey of her generation, Lois Nettleton. One of those people who never quite parlayed ubiquity and recognition into fame – but for all we know that was fine with her.

She has about 15 seconds of screen time here. She made a few score bad movies, currently amuses my daughter as a voice on "House of Mouse." And dig this, "A Christmas Story" and radio-history fans.

Next: Wha?

I won’t tell you how it ends, except to say that’s a little too long and a little too loud. But after Something Happens we see this headline in Variety. Must have made sense to people in 57; heck, it made sense to me.

Ah, the persistence of what we know that ain’t so. Except when it could be.

Oh, the guy with the moustache you didn't recognize? The fellow with the tie and headset and prominent cleft chin? Trust me. You know him.

|