|

I was going to say “here’s a test,” but it seems as if I’ve been doing a lot of testing lately. As if there will be a grade issued at the end of the semester for all Bleat readers. As if you’re supposed to care about the same things I do. Hah! That said, here’s a test.

Does this make you think of a particular decade?

If so, it’s the 30s, isn’t it? Sepia ought to make you think of the 1890s, but often we associate it with the Depression because A) it was the Depression and they didn’t have color, and B) the opening and closing of “The Wizard of Oz.” It was one of my favorite movies as a little kid, and I probably didn’t see it in color until Grandpa got a set. So the opening Sepia sequence, intended to make us think of the rural hardships of Dorothy’s hardscrabble life, was in black-and-white - as was the rest of the film. Didn’t matter.

When you come to the movie as a kid you have no context for the look of things, the Moderne Emerald City, the color palette, the wordless vocals that began the movie, way the audiences would have reacted to seeing the actors in these roles. For you, the Lion was always the Lion, not Bert Lahr; the Good Witch was always Glinda, not Billy Burke. The fact that you never saw any of these people in anything else just cemented them to the characters. The movie was like nothing else and existed out of time.

So: daughter’s school did “Wizard” as their annual play, and it had the usual impressive stagecraft and enthusiastic performances. They included the “Jitterbug” sequence, which may have confused some in the audience: I don’t remember that in the movie. But there were people who laughed at some lines or plot developments, and I thought: you’ve never seen this before? You don’t have this memorized? The woman in back of me snorted with laughter though out, that sort of odd guttural bark that indicates surprised amusement. Really? At the line “pay no attention to the man behind the curtain”? I can understand that if you’d been thinking about hidden forces that manipulate the government to their advantage and are occasionally unmasked by crusading journalists, and then you remember you’re watching a school play and pay attention and that line drops into your lap, but otherwise - well.

After it was done the kids fled to the post-show cast party. I knew better than to seek out Daughter, because the existence of parents is a great shame for middle-schoolers. There seems to be an agreement that they call came out of eggs about five years ago and those older mortifying creatures to whom they are supposedly attached - well, just one of those things you have to endure.

Then I joined the adults to strike the set. I brought my drill and bits, but everything used a torque screw. Or so I learned. “That’s a t-24 torque screw,” said one fellow, who could apparently name it by sight from two feet. So I just lifted and pushed and knocked down stuff, and after an hour Oz had been demolished. I don’t know enough about the theater to know whether this is a practical tradition or one that has symbolic meaning, or both; it’s as if the fantasy, once concluded, must be banished entirely, and the stage made bare for the next set of dreams.

Then I went to a bar for a Ricochet meetup and met many readers of the site: hello! Nice to see you.

And then I went home and worked and sat down with no great enthusiasm to watch “Thor 2,” which I rented because I sort-of like the 1st and Thor’s okay and you have to keep up on these things. Well. Loved it. Perhaps it was just my mood, but that was a nice piece of work. Perhaps one’s more inclined to enjoy a movie if it surprises you early and keeps doing things right, and you don’t notice what you might if you were in a critical mood, but I was just with that one from A to Z. And the “Z” is something else, too.

Back to that sepia picture. It's not fair to say I took it, any more than I took this:

You can imagine that in a coffee table book about Problems in America, can't you. The empty swingset, the two teeter-totter boards pointed up like cannons at the empty prairie sky, the old school with tis window covered with drab panels - you know it's the middle of the country in a place that's not exactly thriving. It's possible the school went out of business. Combined with some other town, because there aren't enough children. Instead of skipping down the street they bounce along on a bus to someplace else.

Is this better?

No, not really, but it doesn't seem to be freighted with MEANING like the other pictures. It's just the school at the end of the street in Tuttle, North Dakota - as seen on Google Street View. Manipulating those images is my new hobby. But more on that later.

Because now: horror.

Hey, it’s a musical! That means good cheer and plucky backstage types and lovable irascible stage managers and cheerful songwriters with a pocketful of tunes. Right?

And it has Professor Marvel, the Wizard of Oz! This'll be great!

It has big Moderne sets that just scream 1939!

It's got big neon!

It's got -

What?

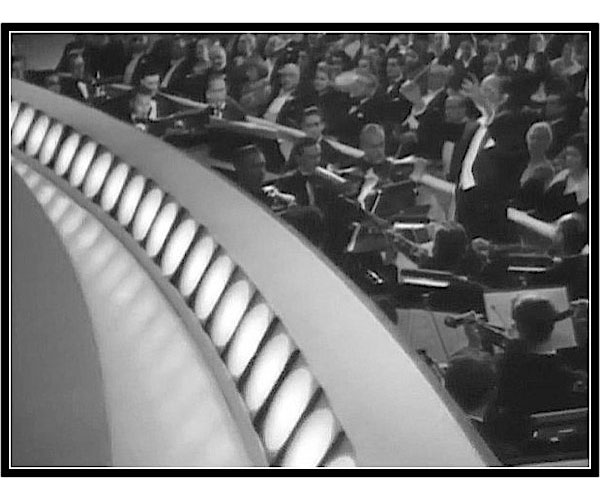

Well, nevermind. That was Jeanette MacDonald up there, disconsolate before the performance, putting on a good face. She misses her old musical partner and husband, Lew Ayres, because they were forced to split up by the screenwriter. He's one of those songwriters who also longs to write a Serious Work, and some of this Seriousness will be on display in the final sequence of the movie. You know how strange it seems to watch a Busby Berkely musical in a movie, and think "There's no way this could be done in a club or on a stage. Impossible. Well, there's an interesting moment in the movie when we glide from the orchestra pit across the lip of the stage . . .

. . . and that transitional device takes you out of the real world of the theater and into the movie world of the big number. It's like a cloud bank that rolls through and transforms everything into fnatasy - even though the world of the movie is, itself, a fantasy.

We begin with a humble shepherd tootling a melody while the Great Composer struggles to complete his work:

Once he hears the shepherd - who's scampered up to the top of the set in the background - the composer is seized with Inspiration, and begins spontaneously composing in a frenzy of creation, because how those artistic types work, don't you know.

Then the stage fills with marching musicians . . .

. . . and singers . . Hey. Hold on. Something isn't quite right.

Something's really not right.

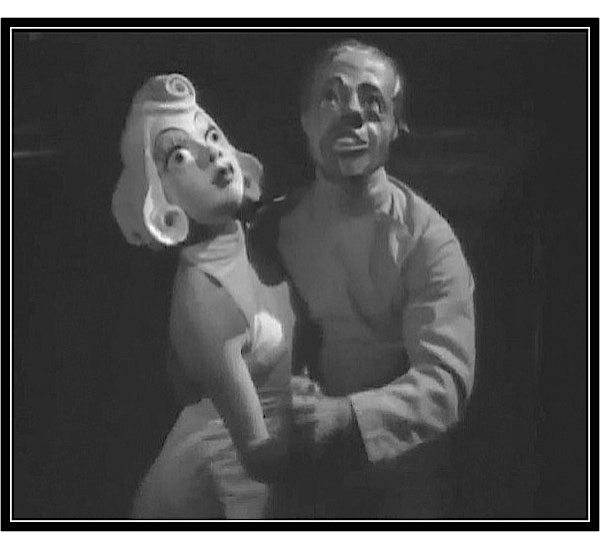

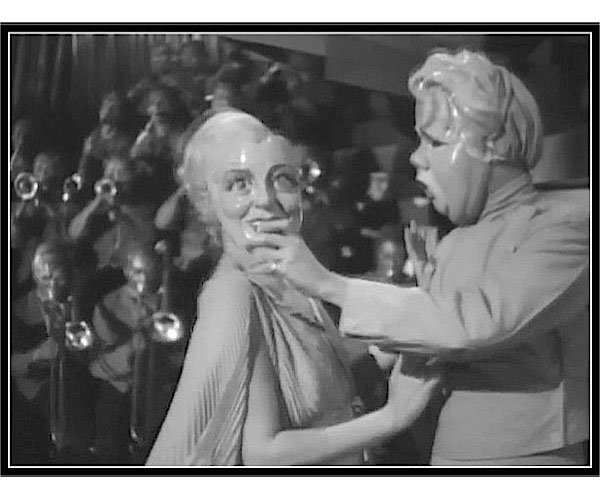

And so we're thrust into the strangest, darkest, weirdest, and unquestionably worst Busby Berkely sequence ever. The masks, made by famous painter and mask-maker W. T. Benda, are supposed to represent various great composers, but all you get is the feeling of being in hell with melty-face monsters and people trapped in grotesque manifestations of their own rotten souls. Oh, and Jeanette MacDonald! Singing and smiling.

My God, it's awful.

Racially enlightened, too! Yassuh!

Now and then a moment of late 30s style that tells you what it could have been . . .

But then it's back to this.

By the way, it's not really in Black and White. Most of the movie is in sepia. Except for a few scenes in red. It ends with MacDonald on a pilllar declaiming the start of a Reich that will last a thousand years:

Well, no, but it's not the sparkling winsome close-up people wanted in a Jeanette MacDonald movie. Let's enjoy some horrifying GIFs, shall we? SEEEEEPIIIIIAAAAA!

Now see the entire sequence for yourself, if you dare.

Work blog at noon and Tumblr too; don't forget the Matchbook update. See you around!

|