Here’s a new concert hall. What does this suggest?

I see an old drive-in. A small town drive-in, stylized and romanticized.

|

|

|

|

|

Now tell me who this is. |

|

|

|

|

|

No? How about now? |

|

|

|

The building above is the Buddy Holly Hall in Lubbock, and those pictures were taken from albums released after he died. I had no idea. It’s almost wrong, like seeing early Elvis Costello in aviator shades.

Saturday we saw “Buddy! The Buddy Holly Story” in St. Paul at the History Theater. It’s a 70s-era place, perhaps late 60s, with the feel of a once-prosperous suburban school. They’ve revived the show several times, because it packs ‘em in. There’s a demographic that loves to hear the old songs, and see a merry tale with the Tragic End.

Everything else runs on rails: the early days, the sudden fame, the Apollo Show, the whirlwind marriage (The third act is almost song-free, as the scriptwriters realized there’s been very little in the way of standard story-telling or character development) and the storied show at the Surf in Iowa.

You really don’t think much about the fact that Buddy Holly, after all that success, was playing a ballroom in a small town in Iowa at this point in his career. Well, he needed the money, since he’d left his old producer and the royalties were tied up for a while. That’s the story.

The plot follows the movie, which was criticized by Holly Experts for the amount of license it took. For example, Buddy punches his producer over artistic differences. Straight-up knocked him in the schnozes over tempo changes. Given that the audience knows nearly nothing about the fellow’s personality or history or anything, aside from we should like him because he’s Buddy Holly and we like his cheerful music, this is a moment that tells you he’s actually not a good man, and has a temper. Right? No! We’re supposed to approve because he has Talent, and believed in Rock and Roll, and wanted to do Bold New Things, but you know: The Man. The Man was keeping him down. The Man was afraid of this new sound.

The punch did not happen. The producer was Owen Bradley, and the play doesn’t give you any idea who Owen Bradley was, and how important he was. It’s the sort of vague cultural recap that makes you boo-hiss the dumb producer, then nod along to a Patsy Cline song played at intermission.

In the end it’s just Tragic Ahead-of-his-Time Musical Genius, which is true except for the Genius part. Don’t get me wrong: he was an innovator, and came up some marvelous work, even more impressive considering his age. But one of the last songs played is “Raining in My Heart,” which has a chord progression that’s outside of the work he was doing. Much more sophisticated. The story sets you up to think it’s his, but it’s not.

So? Well, there’s no harm in cheerful hagiography, Buddy did produce a remarkable quantity of fine stuff, and there’s something decent about the work. You can’t help but think it sounds like something produced by a guy who’d open doors for others and stand up when a lady entered the room, because that’s how he was raised. The show is agreeable enough.

This documentary is supposedly the real thing for learning about Buddy’s life and character. It opens with a silhouette of its producer.

If you knew that was someone famous, and you had to say who it was, could you?

I knew who was involved in the doc, so my mind filled in the information and came up with an identity for this silhouette. How features so indistinct can be instantly recognizable because fame + foreknowledge is one of those interesting things about the brain. About being alive at a particular time. (Hint: it's a Beatle.)

One more thing about the Buddy Holly Hall: this is the sign actoss the street. Made me lol, as the kids say.

He was from Lubbock too.

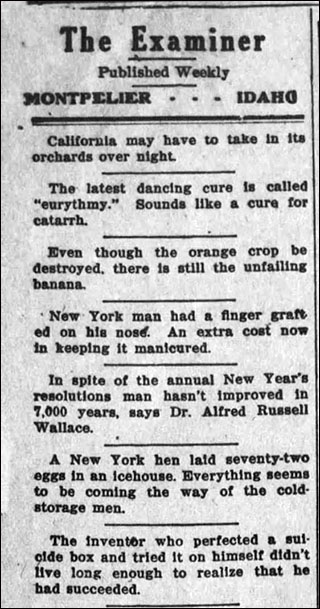

It’s 1913.

Sixteen stories on the front page, including the ever-popular “MANY NEW LAWS BEING PASSED,” which frankly is something of an evergreen.

Front page cartoon:

As the Atlantic wrote in 2011:

Ninety-six years ago, Alexander Graham Bell placed the first transcontinental phone call, ringing up Thomas A. Watson in San Francisco from New York. It was actually a reprisal of an earlier conversation the two men had, The New York Times reported back then:

On October 9, 1876, Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas A. Watson talked by telephone to each other over a two-mile wire stretched between Cambridge and Boston. It was the first wire conversation ever held. Yesterday afternoon the same two men talked by telephone to each other over a 3,400-mile wire between New York and San Francisco. Dr. Bell, the veteran inventor of the telephone, was in New York, and Mr. Watson, his former associate, was on the other side of the continent. They heard each other much more distinctly than they did in their first talk thirty-eight years ago.

That happened in 1915. By the way, the cartoon says “Webster, New York Globe” - our Webby? Bios say he was working for the Tribune at the time, but hey, they could've missed something.

The story:

A wealthy landowner, he was nonetheless an advocate for social justice and democracy. Madero was notable for challenging long-time President Porfirio Díaz for the presidency in 1910 and being instrumental in sparking the Mexican Revolution.

Surely we know something about the deaths now, right?

Following his forced resignation, Madero and his Vice-President José María Pino Suárez were kept under guard in the National Palace. On the evening of 22 February, they were told that they were to be transferred to the main city penitentiary, where they would be safer. At 11:15 pm, reporters waiting outside the National Palace saw two cars containing Madero and Suárez emerge from the main gate under a heavy escort commanded by Major Francisco Cárdenas, an officer of the rurales.

The journalists on foot were outdistanced by the motor vehicles, which were driven towards the penitentiary.

The correspondent for the New York World was approaching the prison when he heard a volley of shots. Behind the building, he found the two cars with the bodies of Madero and Suárez nearby, surrounded by soldiers and gendarmes.

Major Cárdenas subsequently told reporters that the cars and their escort had been fired on by a group, as they neared the penitentiary. The two prisoners had leapt from the vehicles and ran towards their presumed rescuers. They had however been killed in the cross-fire.

This account was treated with general disbelief, although the American ambassador Henry Lane Wilson, a strong supporter of Huerta, reported to Washington that, "I am disposed to accept the (Huerta) government's version of the affair and consider it a closed incident”

Yeah, well, about that Wilson guy. Reviled for his role in the coup.

|

|

|

|

|

Ha ha

Stop yer killin' me |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Some illustrated doggerel. There was so much poetry in the papers of the day.

Not much bio on Mr. Kiser. He worked out of Chicago, and had a book, “Poems that Have Helped Me.” |

|

|

|

Same goes for Mr. Phelps.

Were people more tiresome back then? Did it help to tell them this? Did they listen?

That’s one way of making a pitch, I suppose

That was a lot.

Okay, now there's more. Ten pages of cigarette ads to close out 1955.

|