|

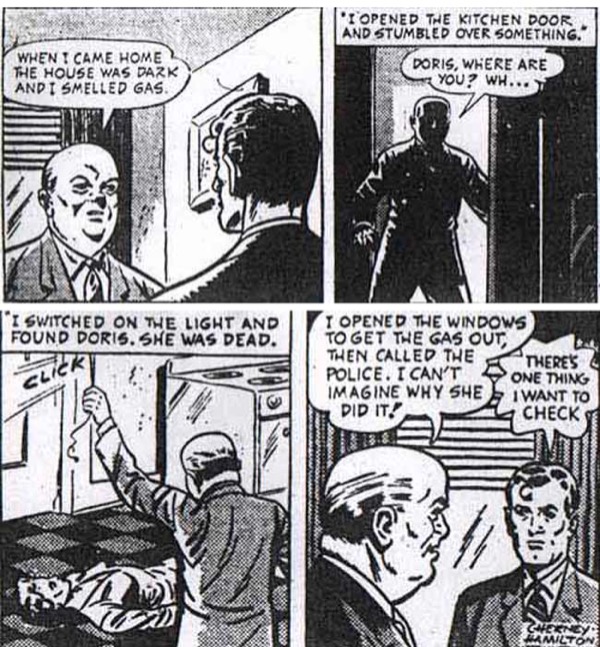

“Fine,” the man said. “You check what you need to check. Checking’s what you boys do.” “Right.” Lawson went into the kitchen. Doris’ body was still laying on the floor. Never wanted gas, he heard the man say in the next room, talking to the investigating officer. Gas can do this do you. You’re asking for it with gas, you are. Always said that. “Right,” the officer said. Lance knelt to the body. He laid a hand on her cheek, felt her skin. The linoleum was warmer. He looked at the window - open. Sniffed - nothing. Checked the pilot light: on. All right, then. He pulled the chain on the light, thinking - I almost hope it sparks. Murder’s worse than suicide. More paperwork. Testimony. Stories in the papers. I almost hope he killed her. It gives you a wrong you can right. Showing up on a suicide call - well, it’s like when the needle gets stuck in the groove at the end of the record. Nothing to do but lift the needle and put the record away. He pulled the chain: no spark. Lance went back to the body. Kneeled again. Her right hand was closed in a fist; her left hand was open. Lance peeled the hand open, wincing; sometimes the hands wanted to stay balled tight, as though they were ready to punch the Devil for the trouble he’d put them through. Or God. Probably God, Lance had long ago decided. The Devil didn’t put anyone through trouble. They were perfectly capable of doing that on their own. She had a ring in her hand. A cheap dime-store ring. It looked like a child’s gee-gaw; given the wear and tear, it probably was. The gilding was chipped and the cheap glass loose in its setting. It was small; Lance tried to fit it on her finger. It didn’t make it past the first knuckle. The man in the next room was talking to Tiny. “All the time,” Tiny said in a flat voice. “Imagine so. Common nowadays. Why, happens in the best of homes. Mental disease, they say. No accounting for it. Runs in the blood. Her mother was just as bad.” “What’s this?” Lance showed the man the ring. “Eh?” He peered at it. Lance watched his face. “Never saw it before. Probably one of her trinkets.” “Look again.” “Why? She had a drawer full of jewelry. I couldn’t tell any of it apart, personally. Not a jewelry man. Gave her an account at the store, left it at that. Why?” “It was in her hand. It might have meant something to her.” “Can’t say what. Looks like a child’s ring, for that matter. Too small for her.” “Do you have children?” “No. Don’t like them, personally. Nothing against those who do. But can’t take the noise, myself.” “And your wife was of the same opinion.” “My wife couldn’t have children,” the man said, drawing himself up as though responding to an insult. As though defending someone, Lance thought. As though defending himself from the glances and whispers of the neighbor ladies, wondering what was the matter with his anatomy. “I see.” Lance set the ring on the table. For a moment he imagined the woman on the kitchen floor twenty, twenty five years before, a young girl sitting under a tree by the school, blushing with furious excitement as her fourth-grade swain gave her a ring he’d saved up to buy. The boy had probably kissed her on the cheek and run away and never dared to say another word. She’d kept the ring ever since. If this wasn’t murder, the ring wasn’t even evidence. Of course, evidence was exactly what it was. Of what - well, she took that with her. “Oh - your wife. Was she right-handed? Left-handed?” “Left,” the man said. Lance thought: ring clenched in her right hand, left hand free to turn on the gas. “Turn him loose, Tiny,” Lance said. “It’s suicide for sure.” “I’m glad you see things clearly,” the man said. “I don’t know quite what I see,” Lance said. He looked at the ring on the table. “But I know you never saw it at all.” |

|

|

SOLUTION: Lance checked the light fixture. It didn't spark when turned on - so the man was telling the truth. If it had sparked before he opened the windows, there would have been an explosion!

|

|

|