|

“How’d I guess. Well.” Lance massaged his temples. He put his hat on the table, and looked out the window. It was a big town, an old town. The new skyscrapers seemed to go straight up to the clouds. He could see the bridge that went across the river. But he couldn’t see his old neighborhood from here. Just as well. It had changed. He didn’t feel welcome there anymore. He - “I mean that with utmost sarcasm, of course," said the man, "since obviously all you’re doing is guessing. Well, if you’re going to make speculations of this nature, sir, I suggest you either corroborate them with empirical findings, or cease to injure my reputation. Even in this private setting, sir, I assure you that libelous statements -” “You did it. No guessing. That’s the facts.” Moron. How stupid did one have to be to fake a crime like this and not think of the most obvious details? Day in, day out; mornings, evenings, late at night, every time: they built their alibis out of tissues and sticks and thought it would support the weight of the law’s heavy convoy. Lance looked back out the window. The bridge looked just as it did when he was a kid. Just as tall. Just as wide and proud. A highway to the new world in the city, out of the petty world of his neighborhood, into a cosmopolitan playland of nightclubs, dance halls, long-legged girls with Veronica Lake hair. (Veronical, his friend Frankie always called the actress, and it came to be an adjective in his neighborhood: my, don’t she look Veronical.) Where was Frankie now? Dead, or jail. Like most of them. A few stayed; most moved out. Most of their parents lit out for Leavittown when the blacks started coming in. Not to say the old neighborhood had been paradise - Christ, he got his nose pushed in a dozen times for not being Wop like the rest of the boys around the corner, but at least they were all red-blooded Americans, you know? Not that he had anything against the races. Helluva Chinese restaurant around the corner from his apartment; nicest people ran it. Had to arrest their son once, and it broke his heart. But - it just did something to him when he went home, and he saw all the old places: the school, the yard, the park, the apartments, the stores, the corners - and everything was the same, but it was all someone else’s now in someone else's lingo and he couldn’t even get out of his car and walk around the neighborhood - his neighborhood! - without hard looks and someone spitting on the ground as he passed. It was like everything had been blown apart, blown into atoms, but it was still standing like nothing happened. “I said, either state your reasons or get out of -” Lance spun around and clipped the man on the face; he angled his hand so his class ring caught the man’s lip. The man went down without a sound. Lance left the room. The officer in the hall looked up. “Might want to call a doc,” Lance said. “He threw himself on my mercies and cut himself.” Later that night, at the Chinese place around the corner, Lance had more to drink that he usually had, and it wasn’t until the restaurant was completely silent, and everyone was looking at him, and his own loud words - SPEAK AMELICAN, YOU GODDAMN GOOKS - were still hanging in the air, that he realized he could never go here again, either. |

|

|

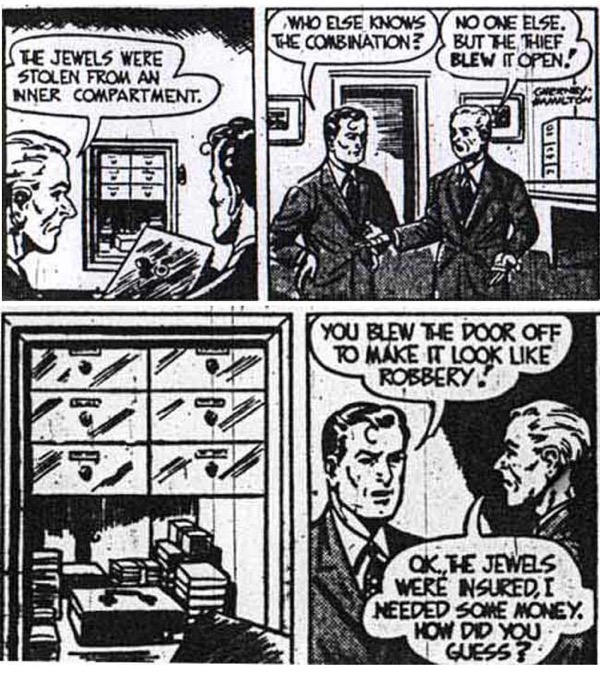

SOLUTION: "Lance guessed the safe had been rifled by someone who knew where everything was (the inside was orderly) - and the contents hadn't been disturbed by the explosion." |

|

|