You will have to bear with me while I go quietly mad, because I am hooking up a new computer. Two monitors. I used to have a Mafia nickname at the office: Jimmy Two Screens. Back before that was popular. Once you get used to all that . . . that what? Right, real estate, you can’t go back. I decided against the iMac, because it’s smaller and underpowered compared to the Mini, which is counterintuitive but there you have it. I’m sure a 27” M2 will be announced in 15 days, when the return window closed.

What the Mini does not like is my USB hub, for whatever reason. It will see the Time Machine drive, but when asked to accept the password, it mums up and says “nope. Don’t like it. Don’t know what’s in there. Ark of the Covenant stuff for all I know. No sir, I don’t like it.” All drives are functional, but the hub - AND YES IT’S POWERED - seems to be arguing with the Mini. Which means, maybe, going on Amazon and wading through 1,305 pages of Chinese made hubs, each from a different company, each dedicated to making my life happier (see attached photo of man on sofa smiling at his laptop having happier life).

The grand scheme was to have an HMDI switch box that would let me effortless toggle between the main monitor and my gaming PC, which I have not touched in a year, at least. Why? Because A) it’s such a bother to swap out HDMI plugs, and I had to get out a different keyboard and face in slightly different direction, perish the thought. Well, I hooked up everything, and the PC . . . it does nothing. It turns on. It does nothing. It does not chime, the fan does not start, nothing.

So I’ve actually lost functionality. The Mini also seems to forget which screen is the primary screen. So all in all, great day.

No really, it was! Just weary of poking around behind the desk and threading cords and testing and hoping. Well, I’ll fix it all eventually. For now, though, there’s the joy of reloading everything on the new computer - a task that’s gone smoothly, I’m happy to say.

I went to the produce department to get some salads. A burly fellow was restocking the Fresh Express Kits, which come with toppings and dressings.

“Hey,” he said. “Are you still teaching?”

“No, don’t teach,” I said. “I work at the newspaper.”

“Right,” he said. I think I’ve seen this guy at this store for 15 years. I know his name. We rarely talk because he’s not a talkative sort, except every few years he’ll strike up a conversation. So we talked about the newspaper and about salads. I learned he has a wife.

I was in another aisle a bit later, and decided I really didn’t want the Pesto Fresh Express salad kit. Besides, the date was too close. Expired next Tuesday. I went back. He was still stocking.

“Did you ever know Sid?” He asked, referring to our sports columnist. Suddenly “Fly Like An Eagle” sounded from the speakers above: DUHUDLA-Dut-dut, da DULUD UT DUT

“Steve Miller calling,” I said. “Anyway yeah, but not so much.” True: I’d worked at the paper a quarter-century and Sid gave me not a nod. I remember when we left the old building and had a rally, and he made a speech praising the guys who hadn’t owned the newspaper since the late 90s, and how they were responsible for saving Minneapolis by championing the urban renewal that razed dozens of blocks of the old city. Hooboy hokay. Well, he was ninety-something.

IIRC, he retired when he hit 100, and there was a big goodbye party scheduled in the new building’s atrium, right when COVID hit. The commemorative photos of his career stayed up in the lobby for two years. They have since been replaced by pictures from a big story about wolves. His office is still sealed and full of his stuff, like King Tut’s tomb.

I kept shopping. Great BOGOFs. Saw a man circling the new salad bar with a strange intensity, as if he was pressed for time and could not believe they were low on garbanzos. There had to be more garbanzos on the other side. But no! I chatted with the deli guy about how it was odd that the Cole slaw was priced by the pound but sold by volume.

In other words, an experience deadened by consumerism and tainted with the unspoken implications of class privilege.

Eh? What? Well:

A French author takes a critical look at grocery stores, and as you might well expect, finds them wanting.

Through observation and analysis that feel nearly anthropological in their detail, Ernaux argues that our shopping habits are determined not by personal choices, but by factors that are frequently outside our control—our financial situation, our location, what products we have access to.

You don’t say.

Supermarkets were supposed to be great equalizers, democratizing food access, but they have instead become a microcosm of contemporary consumer malaise.

Malaise, in France? C’est impossible! Now, that might well be the case, but I’m sure we’re going to be asked to extrapolate and assume that US grocery stores suffer from the same ennui, only dumber.

Ernaux’s departure from the intensely intimate relationships that are the focus of much of her previous work might feel unorthodox at first. But as her gloomy portrait of the big-box store begins to form, it becomes clear that this book isn’t so different from her others: Her interest lies less in the store itself than in the way it serves as a site for interpersonal interactions.

You mean, the author provides a series of assumptions made about people with few specifics.

EXAMPLE

The guiding principle of a store like Auchan is that everyone can get what they want, whenever they want, quickly. In practice, the supermarket is no freer of class hierarchies than the world outside it.

Yes. And? So? Would they prefer one that has explicit class heirarchies, and freezes out the less-endowed sectors with uniformly high prices for top-shelf foodstuffs? No meat department with a wide variety of cuts, only Wagu beef. Because that would solve the problem.

For instance, Auchan’s bulk-sweets aisle is riddled with signs prohibiting on-premises consumption. This wards off theft, theoretically, but to Ernaux this action is inherently classist—“a warning meant for a population assumed dangerous, since it does not appear above the scales in the fruit and vegetable area in the ‘normal’ part of the store.”

This might have something to do with the store’s experience, and the cumulative experience of the industry.

Anyway, the presumed “samplers” aren’t more dangerous. Also, I’d bet there’s something about the size of the bulk-sweet items that encourages sampling. One is more likely to justify swiping a single M&M than a whole banana.

Perhaps? Nay! Class warfare.

Then something-something about interacting with other ambulatory meat-sacks, ergo

Experiences such as these are, for Ernaux, the only redeeming quality of the one-stop shop; by describing them, she reanimates a shared humanity that consumerism has flattened out.

I too miss the robust shared humanity that preceded “consumerism,” and people met together to do things like slaughter each by the thousands on a battlefield.

Contrasting a stray shopping list left in a cart with one’s own, as Ernaux does, might strike some simply as nosiness; but seeing oneself in another’s choices is radical in its quiet way.

It is neither nosy nor radical in any way. It is pretentious in many.

In one scene near the end, Ernaux cuts up an Auchan rewards card, incensed at the condition that self-checkout users must present it or be subject to random inspections by store workers to make sure they’ve paid for everything. In the hands of a less skilled writer, this might come across as vapid or performative. In Ernaux’s telling, the gesture feels reasonable and justified.

I’m stunned that the writer would present the episode in a way that justifies the writer’s ideas.

I don’t know about this card - do you present it to the machine when self-checking out? That seems to be prerequisite for getting certain bargains. How does presenting the card ensure you’ve paid for everything? Do you wave it at the worker? Present matching ID?

Unhappy with the world, unhappy with abundance, unhappy with life, unhappy with one’s self. Everything is wrong. We saw essays like that in abundance pre-COVID, when miserabilism was the sign of the enlightened. The people who wrote them quickly shifted to the front lines of Safetyism, but that doesn’t sell anymore. So it’s back to walking into a modern grocery store, full of goods from all over the world, restocked constantly, full of gustatory opportunities unknown to just about everyone else in the world for the entirety of human history, and finding a way to sneer.

It’s 1960.

That’s one fug-ugly front page.

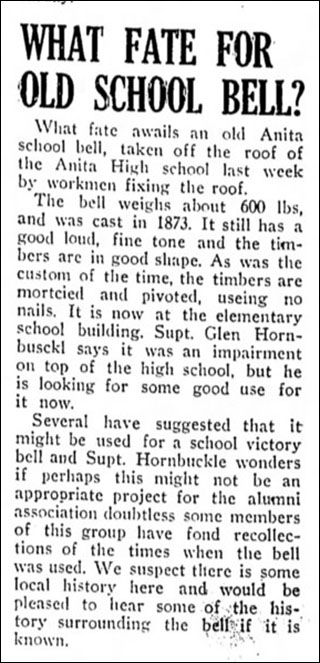

This is a big deal in a small town:

| |

|

|

|

|

It appeared that people were not stepping up and doing their part. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What fate, indeed. A bittersweet little story, no?

Especially since it’s hard to say what became of it. Google “Anita Iowa” and “school bell” and you get a lot of hits on a 70s disco song. |

|

|

|

The end of an era and a startling break in community continuity:

These were the voices that answered the switchboard and placed your calls and called you back when a line was open.

Pearl’s daughter, who died in 2018, followed her mother’s example and was a schoolteacher.

Wiota was, and is, a tiny town about ten miles from Anita. I wonder where the phone company was.

| |

|

|

|

|

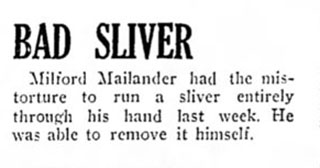

Yeeeeeeeouch |

|

|

|

“In Amazonscope.”

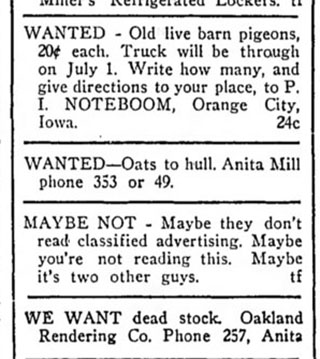

Finally: the classifieds.

|

|

|

|

|

Give us your barn birds. Also dead animals. Why? Hey, isn’t it enough that I’m takin’ ‘em off your hands? |

|

|

|

And that's about it for Anita in 1961.

That'll do. Now it's time see what the floors looked like in the 50s.

|