|

|

The day after the event, and I can’t speak. Completely blew out my voice, yelling for seven hours. I sound like a gangster. Jimmy Gravel. It was great fun, and met many interesting and lively people - including some Bleatniks! Which is always fun, except I have no stories to tell then, because they know everything. What I do not like is having to shout, constantly, to be heard over the racket of everyone else shouting. Don’t even remember if there was music; just remember the din. You wonder what would happen if the establishment periodically sounded a siren, quietening everyone, then let one segment of the bar start to talk, admonishing them to do so in a neutral voice. Then the next segment. Repeat every half hour as people started talking over one another again.

Finding the event was amusing, since we were bade to meet at the City Vineyard NOT the City Winery, that was a different place. The location:

Well, I met a fellow (Bleat reader and Ricochet member - two stamps on the visa) upstairs at the City Vineyard. The staff didn’t seem to know anything about the event. Then I noticed that the staff had shirts that said City Winery. Ah, dammit, we’re at the wrong place. So we went downstairs to sit and wait for the organizer, who was texting me with notes that it was WINERY, not VINYARD. Whereupon I saw a sign:

|

|

|

|

|

So . . . we were at the right place? They were the same? But no: the sign suggested that the CITY WINERY was elsewhere, and this place was by, as in a product of, the Winery. |

|

|

|

Two other folks showed up, figured out it was me, and showed an email noting that the group co-hosting the event had decided to move it a mile north at the last minute.

Huh. Hmm. Well. Eventually we all coalesced in the same spot and commenced to yell. It was the sort of event where you’re talking about Freudian approaches to schizophrenia then architecture then Genesis then old movies - although in the last case, the fellow with whom I chatted was younger by a significant degree, and “old” meant 70s. It was an interesting argument, since he held the 70s as perhaps the greatest era of American film, and I took that with a wince, a wince that was audible over the noice, and so we set to it. The movies we discussed were quite good, but I still think the studio-era products were more dependable on every level as story-telling machines. The B movies had drive and structure. The B-level stuff of the 60s and 70s were indulgent attempts that took advantage of the loosening of the form, and did not profit from it.

After the event we went to DeNiro’s restaurant, the Tribeca Grill.

Somehow that turned into four hours at the bar. Great time. Then I walked back to the hotel in the rain and the mist at 10:30.

Today’s building: 20 Exchange, intended to be the world’s tallest building.

We rarely think about these things anymore:

The fifteenth floor was devoted exclusively to a telephone exchange.Telephone engineers considered the exchange to be the world's largest, with 37 switchboard operators connecting with 600 trunk lines and 3,600 extensions. The rest of the building was similarly technologically advanced. For instance, soap was stored in a basement reservoir and pumped to every bathroom sink.

There was a guy whose job consisted of keeping the soap distribution system going. I wonder if he had help.

This is surprising, somewhat:

After the merger, City Bank Farmers Trust commissioned a new structure at 20 Exchange Place to house the operations of the expanded bank. At the time, several skyscrapers in New York City were competing to be the world's tallest building, including the Chrysler Building, the Empire State Building, and 40 Wall Street, none of which were yet under construction. 20 Exchange Place was originally among those contenders for that title.

According to the Architectural Forum, the design process had to be "a coordinated solution to complex mechanical problems and the strenuous demands of economics", with aesthetic considerations as an afterthought.

The designs still looked nice.

It was downscaled from 71 stores to 59 after the crash, and aesthetic considerations crept back into the design. It has a lot of nickel ornamentation, and the Giants of Finance at the top:

Beehives, a symbol of industry.

Now. Consider that structure, the way it steps back, the way it glitters, the ornamentation, the symbolism, the restraint, the enormous weight of stone and steel, the way it connects to the evolution of the form over the last 20 years.

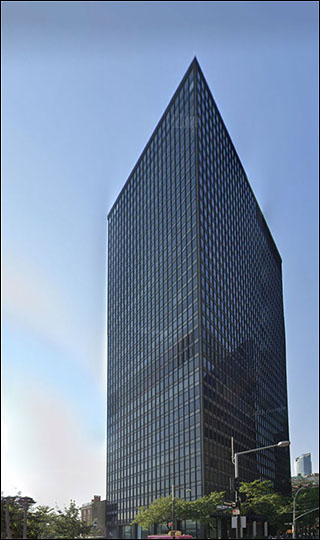

Now consider this.

It’s 55 Broad, 1966, designed by Emery Roth. Well, his firm. He was long dead, but the firm continued on, turning out one Mad-Men era skyscraper after the other. Roth got his start working on the Columbian Exposition of 1893, where he turned out some lovely little classical structures. The impact of his firm, however, did not enhance the historical traditions of the city.

To put it kindly.

If there’s one thing I want you to take away from all this, it’s the destructive effect of the over-application of the International Style. This will take a little time, so bear with me.

But the reality, repeated over and over, has a dulling effect. Consider the twin:

|

|

|

|

|

It’s just a nothing box. It's by Emery Roth & Sons, like the ones above.

Now move across the street . . . |

|

|

|

|

|

55 Broad again, to remind you of the firm's kaleidoscopic variety. And this one takes up the entire block. Just boxes stacked on boxes, a literal expression of the zoning envelope. Thou shalt step back here, and here. Considering the neighborhood, with its collection of small-scale 19th century buildings, these are interlopers, rude impositions. |

|

|

|

|

|

Oh look, down the street a ways:

It’s by Emery Roth. |

|

|

|

|

|

Well, what do you know? Gosh, I wonder who designed this one. |

|

|

|

|

|

Let us wander towards Battery Park. Can you believe it? This one's by Emery Roth & Sons! Who'd have guessed! |

|

|

|

|

|

3 Hanover. People tired of the black boxes, and the early 70s style switched to this.

It's by Emery Roth & Sons, so you know they were completely flexible. |

| |

|

|

Okay. Keep this in mind as we explore something else.

This is the battle, right here. |

|