A reminder: we are in New York this week of Bleats, and we are going to learn about buildings you've never heard about. Why? Because they are testaments to American civilization, and a reminder that behind many doors in Gotham are extraordinary spaces. So very many spaces.

A few notes before we begin: I stayed at a Mariott / Bonvoy Whatever on Pearl Street. It was not an old hotel upgraded for the 21st century. It was not an office building rehabbed for travellers. It was a by-God modern hotel built in recent years, so it had larger rooms and big windows. It was good. But like many hotels these days, they didn't do anything absurd as clean your room every day. For that matter, they didn't clean my room at all, ever. You had to request service. In a way, that's fine - I always feel as if I have to get out of the room so housekeeping can do what they need to do, and if you come back from a long jaunt and the bed is still unmade, you feel a great sense of things unresolved and unfinished. I only needed more shampoo and soap, since the provided containers were single-use, and more in-room coffee. Keep those packets coming. It wasn't great but it was coffee.

The neighborhood had more life and retail and food than I'd expected. Many blocks were marred by sidewalk sheds, though - scaffolding over the sidewalk, like some Batman movie vision of Gotham decline and perpetual ineffective maintenance. My hotel wasn't being renovated, but we had the scaffolding. Some of the struts were screwed the ground, as if permanent.

What I learned from googling: the facades are inspected every 5 years, and some places leave the scaffolds up and hope they don't get fined. Some have them up because, well, who knows when a chunk of masonry might dislodge. It's not a good thing. The hotel went up in 2017; the google street view from last year shows the scaffolding up. It's as if never took the bandages off.

Lots of dogs. So many dogs, and so many big dogs. Do they sit all day in small rooms up in the sky?

SO MUCH WEED SMELL

Not as many retail vacancies as I expected, but a lot. Overall mood of the area: active, well-maintained, and safe.

We return now to our visitation of the buildings of New York that are not Chrysler, Empire, or WTC.

I saw I was on Barclay street, and wondered: might I also be near Versey? Duh, you say. Bear with me. Long ago, when I found my enthusiasm for the 1920s and the architecture of the era, I was interested in the Barcley-Vesey building, because everyone at the time seemed to be interested in it. I didn’t see why, exactly, but you were obliged to be able to say “Ah yes, Barclay-Vesey, an influential Arc Deco skyscraper.”

Influential, perhaps, because of its plainness? Its massing, the way the tower adheres to the grid but the body of the building aligns with the streets?

Built from 1923 to 1927. Hammered hard on 9/11, reconstructed at a cost of $1.4 billion. Now, of course, it’s residential. Anyway, back to its reputation:

Mumford said that the design "expresses the achievements of contemporary American architecture...better than any other skyscraper I have seen."Joseph Pennell called the Barclay–Vesey Building "the most impressive modern building in the world",and Talbot Hamlin predicted it would be "a monument of American progress in architecture.”

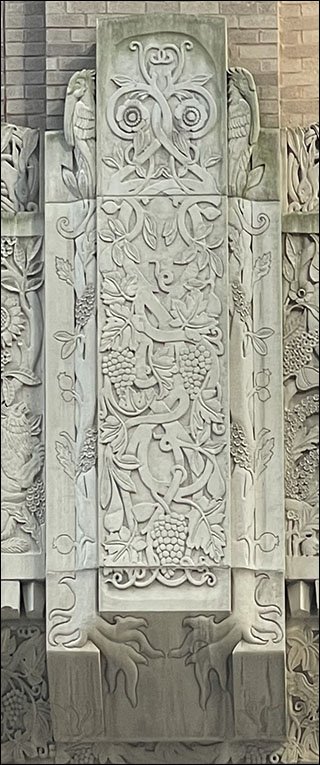

I think it’s because it did less. Not a lot of showy exterior ornamentation, but there’s some great carvings over the back door.

| |

|

|

|

|

The carvings make up for the plain stark expanse of curtainwall, frosting on a brick. |

|

|

|

|

|

It was the New York Telephone Company’s HQ, by the way. Hence the Bell. |

| |

|

|

I went inside and chatted with the guy at the desk, who was the nicest lobby guard I’ve met so far this trip. And I’ve met a few. I always ask if I can take a picture. Most say no and don’t understand why I would want to. They all say the same thing: 9/11. Yes, that’s what the hijackers used to hit the towers: tourist photos.

The guard said a professor had been by the other day with a tour group, and he’d learned some things about the building. It was designed by a man named Franklin (it wasn’t; Ralph Walker) and it was older than the Woolworth Building.

AND THEN I JUST HAD TO BE THAT GUY

“Nooooo,” I said. “It was built about 15 years later.”

“Really?”

“Well, you have one of the nicest places to work, I’ll say that.”

He sighed. “Too dark, with my eyes.”

It’s much more ornate inside than I had expected. Like stepping into a French tapestry, in many ways.

There's something about this shot I can't get my head around - a strange mess populated with fragments of different places.

From there I went to the Equitable, one of the most important and influential buildings in the history of modern architecture.

You may say . . . really? That thing? Why? Well, I’m glad you asked. It’s 40 stories tall. Humans for scale:

It was built in the teens, and was an absolute brute compared to everything else extant. The giant file-drawer style cast shadows for blocks, they said, and urbanists of the day were concerned that a city composed of these beasts would plunge the street into darkness. So they passed a law that mandated set-backs as the building rose, and that led to the American style of skyscraper, reproduced in cities around the country that had no fear of Equitable-sized office blocks plunging main street into the Stygian night.

I went inside for the first time. There were two security guys who looks like old-school goodfella enforcers, and I asked them if I could take a picture.

“Yes,” said the largest and beefiest of the two. “And thank you for asking.”

“Some buildings don’t approve,” I said.

He nodded. “Nine Eleven.”

The Equitable stands by the Trinity Church and graveyard.

|