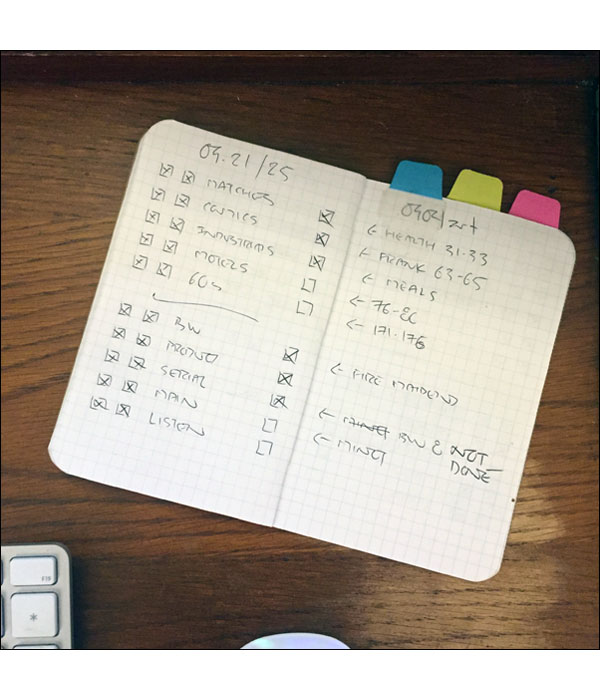

Column night, the usual excuse. But there’s a long and pointless thing below, and Motels, and Main Street, so I don’t want to hear any kvetching. Not that you would. By the way, I’m extending Motels into October, with fewer entries. Why? Because I have this little Field Notes book in which I map out all the sites and features, with little boxes for LAID OUT / WRITTEN / UPLOADED. I wrote MOTELS for Thursday when doing next month’s Bleats. (They’re all laid out.) I can either ignore it, cross it out - messy! - or rip out the pages and redo the OCTOBER section, and all those options are unacceptable. Column night, the usual excuse. But there’s a long and pointless thing below, and Motels, and Main Street, so I don’t want to hear any kvetching. Not that you would. By the way, I’m extending Motels into October, with fewer entries. Why? Because I have this little Field Notes book in which I map out all the sites and features, with little boxes for LAID OUT / WRITTEN / UPLOADED. I wrote MOTELS for Thursday when doing next month’s Bleats. (They’re all laid out.) I can either ignore it, cross it out - messy! - or rip out the pages and redo the OCTOBER section, and all those options are unacceptable.

You think I’m kidding?

I’m not saying I work in advance, but I have the art for the Bleats chosen through DECEMBER of 2016. I have so many updates and new sites ready to roll the entire first half of the year is full. And I do some of these things knowing no one will care, but since I like to think of this site as a big undisciplined museum, that means card catalogs. And that means pages like this, fully updated, with links to all the Main Street functions.

Boy, this is a riveting start, isn’t it. Well. Slow easy day, gloomy and warm. Rain now and then. I’m in the gazebo with slumbering Scout, who spent last night on Raccoon Duty before realizing his nemesis wasn’t showing up. Oh: about that “dogs don’t feel guilt” business. Tuesday I came home to discover a shattered dish on the floor, Fiestaware no less. Five muffins had been on the plate when I left. I said nothing. Scout was sitting by the door, which he never does when I come back. He was the picture of regret, looking away, tail thumping, ears back. I had no threatening words or posture; I just looked at the dish and looked at him. HE KNEW.

Half an hour later he was on his back in the grass in the sun, playing with a bone, the very picture of frolic and joy; made you happy to see his happiness. I don’t get people who don’t get dogs.

.

Then there’s this, in the Paris Review. I love the site, but man, sometimes. Some times.

The writer / interviewer's questions, which often aren't, will be in italics. The subject's responses will be in regular, stand-up-straight type. Explanatatory passages from other sources in sans-serif. It begins:

Joanna Walsh’s writing enacts what Chris Kraus has called “a literal vertigo—the feeling that if I fall I will fall not toward the earth but into space—by probing the spaces between things.”

Do you know what that means? Has anyone reading Walsh ever experienced literal vertigo, or is “literal vertigo” a figurative expression for some sort of psychologically disorienting revelation that comes from probing the space between things? And is there anything more pretentious than finding some revelatory quality about the spaces between things? There are spaces between all things. Oh look, there is a space between my computer and the cup that holds some pencils. Between them, in the space, a Post-It note pad, empty of jottings. It stands as a symbol of potentiality, yet neither the computer nor the pencils can write upon it, for the pencils are - SYMBOLISM COMIN’ RIGHT UP - unsharpened.

We continue:

Walsh, a British writer and illustrator, is fascinated by liminal spaces, especially in the many varieties encountered by tourists. She’s sometimes known by her French nom de guerre, Badaude, loosely translated as “gawk,” and suggesting the perambulatory figure of the flaneuse.

That would be the female version of this:

You may be familiar with the flâneur, a nineteenth century French character depicted by writers such as Balzac and Baudelaire. The flâneur was top-hatted and carried a long cane; he was a dashing young gentleman whose literary prowess allowed him to describe and analyze social customs, art, commerce,and politics in the modernizing city.

Back to the piece:

Among her seemingly disparate subjects are hotel architecture and etiquette, sexual politics in twentieth-century psychoanalysis, the perils of family vacations, the fantasias of cinema, and fables of transgendered witches. In Walsh’s feminist cosmogony, all are brought to bear as inscrutable souvenirs of the everyday mundane.

I'm a big fan of the everyday mundane and its souvenirs, although I don't find them as inscrutable as some people might. But no one cultivated an era of mystery and insight by bringing plain old souvenirs to bear.

She elucidates the slippery, gendered in-betweenness of everyday ritual in a manner reminiscent of Derrida’s disquisition on the chora—that most mysterious and mundane of spaces, not unlike the anonymous corridor of a hotel.

There are gendered in betweenness of everyday rituals, and then there are slippery ones. How firmly one may grasp the in betweenness of rituals that occur with lesser frequency, I don’t know. Who could possibly care about the sexual politics of 20th century psychoanalysis can possibly be learned by googling, but I suspect the image-search result is going to return a lot of New Yorker cartoons.

The interviewer says:

The hotel becomes a kind of disorienting counterfeit to the authentic shelter of the home, which is the dominant space of traditional Western values because it’s a place of permanent or rooted dwelling—in the Heideggerian sense of the word.

Yes, that’s a question. Let me admit something that may betray the ankle-deep nature of my soul: I have never been disoriented in a hotel because it was a counterfeit to authentic shelter. For one thing, having seen the rain beat against the window glass and having heard thunder boom above the rooftops beyond, I have concluded it was, after all, authentic shelter. Whether it was authentic in the Heideggerian sense is another matter, of course.

Or, for that matter, whether the Heideggerian concept of authenticity is authentic. Here's a high-falutin' phee-la-sophy page to explain it for you.

The most familiar conception of “authenticity” comes to us mainly from Heidegger's Being and Time of 1927. The word we translate as ‘authenticity’ is actually a neologism invented by Heidegger, the word Eigentlichkeit, which comes from an ordinary term, eigentlich, meaning ‘really’ or ‘truly’, but is built on the stem eigen, meaning ‘own’ or ‘proper’. So the word might be more literally translated as ‘ownedness’, or ‘being owned’, or even ‘being one's own’, implying the idea of owning up to and owning what one is and does. Nevertheless, the word ‘authenticity’ has become closely associated with Heidegger as a result of early translations of Being and Time into English.

So does the hotel room own up to what it is, and does? Yes, every time you get out a key to buy something from the fridge, which is a revelation of the commercial nature of the stay, and a sharp break from the relationship between you and your own fridge

I'd also posit that hotel rooms are not disorienting, as they strive to give you something familiar every time, decorated with choices and objects that do not reflect the nature of your own home, and hence cannot be mistaken as a crafty simulacrum. Every room has a bed, or two. A desk, a television. A chair. These are all in arrangements that are distinct to the hotel room.

Go back to this: the dominant space of traditional Western values because it’s a place of permanent or rooted dwelling.” Are homes in China the dominant space of traditional Chinese values, or the values that have arisen since the country shifted to a more liberalized economic system?

And we haven't even gotten to the subject's responses. Part of the her response:

Hotels are all about defined choices. A refusal of desire leads to a lack of definition. Homes have a lot of blank spaces. It’s easy to get lost there.

The other day I found myself trying to walk through a wall that didn’t have a picture on it. Utterly confounding. The feeling of being lost in my house was literally vertiginous.

Read that quote again. Wonder if you’re missing something? If I’ve removed context? Guilty as charged. Here’s her point.

Unless we’re engaged in a constant struggle for basic necessities—and thank goodness I’m not—we live in a world in which desires claim a massive role. Desire involves definition, choice, and rejection. Hotels are all about defined choices. A refusal of desire leads to a lack of definition. Homes have a lot of blank spaces. It’s easy to get lost there.

Got it? Good. No?

To which the interviewer says:

If we could shift our traditional notions of “placeness” from the home to the hotel, we could find a new way of considering modern space.

Is it generally understood amongst the Thinking Class that the old way of considering modern space is inadequate to contemporary requirements? Or is this a case of wanting a new way for the sake of having new way? If you have a new way, then you can enjoy it as you walk around - sorry, inhabit modern spaces, and you can smile to yourself as you realize other people are using an old way of considering modern space.

Especially as these spaces relate to Placeness.

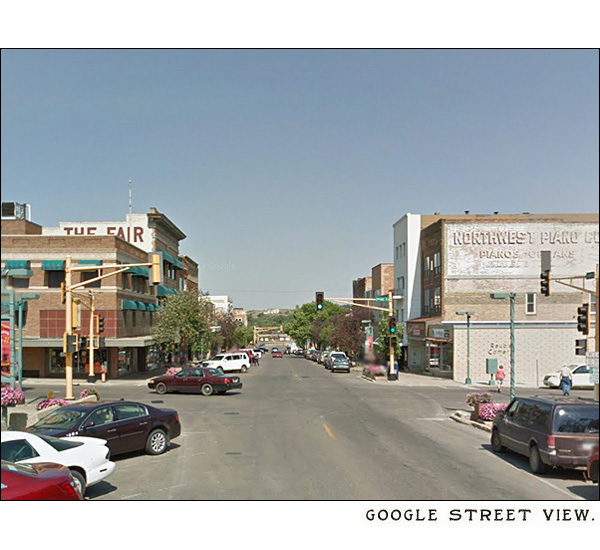

I've been here, but it's been a while. Nice to see the Google Car made it in summer; come the winter, the roads are impassible for days, and residents have to rely on dried beef and canned beets.

Or some think, this being North Dakota.

That's a perfect shot of a small-town downtown: the 50s renovation on the left, the faded sign, the three-story structures. Let's see what's around.

I don't think you'll find a piano, but you can drown your sorrows at Reub's Comer. Or Corner. Google Street View has a way of playing with kerning.

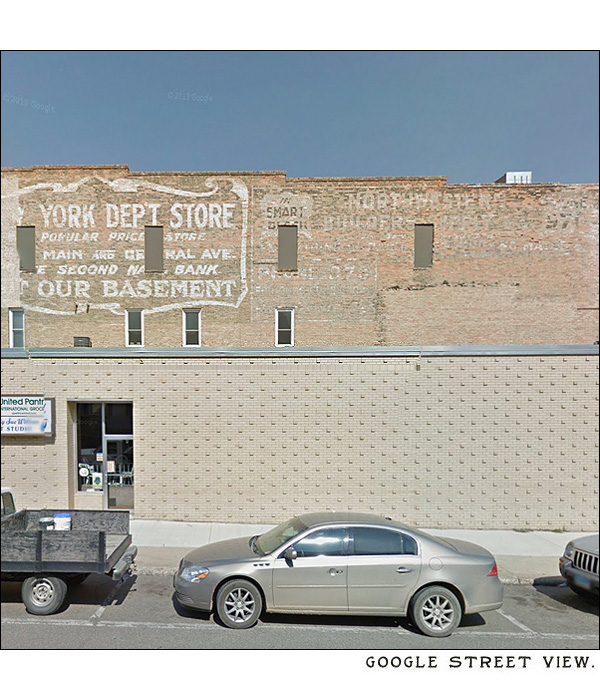

Below, the rest of the side of the building:

The New York Department Store. The rest of the sign just trails off, although you can glean "The Smart Block" and perhaps more Northwestern Piano paint.

Old ladies still remember that place, I guarantee it.

"Look for the Horse standing on the turquoise awning" should have been their slogan.

That sign: I hate those signs.

They were everywhere, for a while. Three panes, one globe. Ugly and cheap.

Nice piece of International Style 60s chic. As I always say - well, not always; depends on the context, of course - you can't go wrong with one or two of these. Thirty is another matter.

Nice piece of 1940s facade modernization, to show what they thought the simplified future would be like. Either words for me.

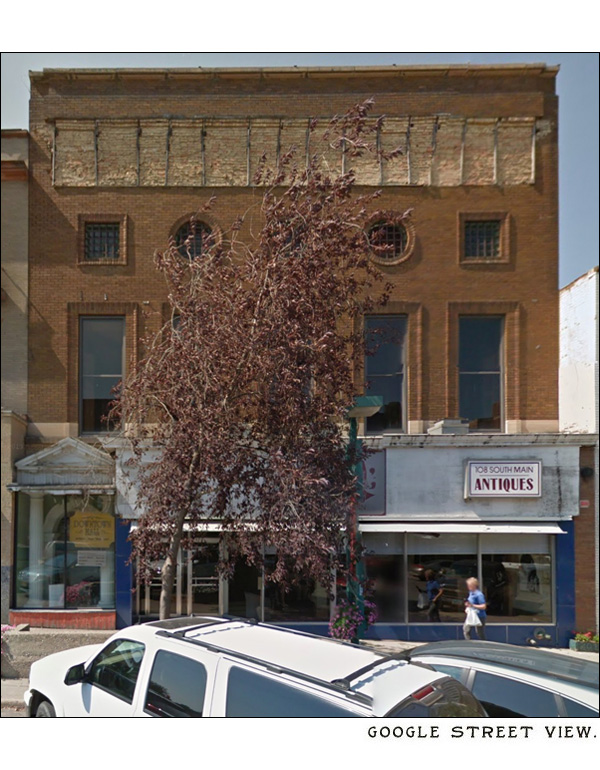

In ancient Egypt, the only way to remove evidence of discredited rulers was chiseling out their likeness and any heiroglyphs, eliminating their very existence. Anyway, here's a building in Minot:

I've no idea what happened here.

How lovely. Except I don't know why they stuck the sign there.

Don't expect the interior to reflect the signage, because I googled the place, and it doesn't. But they seem to realize that the place is a local landmark, and I'm guessing the swank sign has a lot to do with it. Minot! A space-age city on the move!

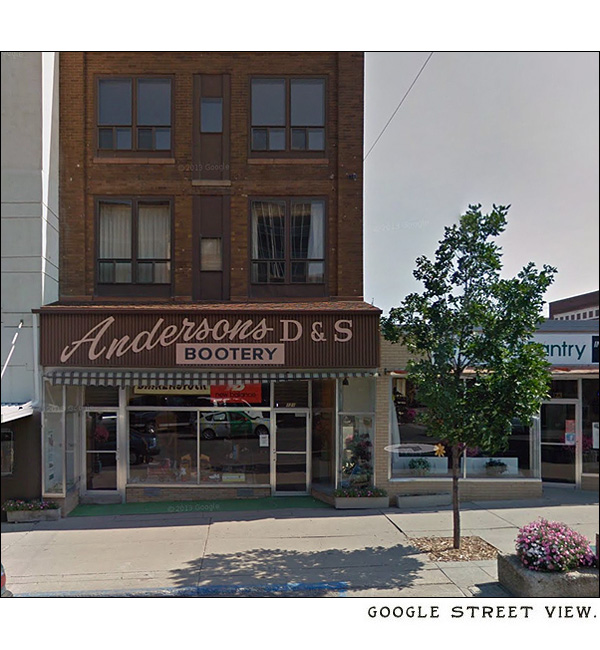

We had a Bootery in Fargo. All towns probably had a Bootery. Minot had a D&S Bootery.

There may have been other D &S Booterys, but this one belonged to the Andersons.

Crenellate like there's no tomorrow, boys - old man Blakey's picking up the tab!

You know, of course, that there were big broad windows letting in light and air, and it looked much friendlier. But that had to be changed, because . . .

. . . because . . .

Well, it'll come to me eventually. The building was designed by this fellow:

Robert Stacy-Judd (1884–1975) was an English architect and author who designed theaters, hotels, and other commercial buildings in the Mayan Revival architecture Style in Great Britain and the United States. Stacy-Judd's synthesis of the style used Maya architecture, Aztec architecture, and Art Deco precedents as his influences.

All the way from England, to Minot.

Another example of bad window updating: now you have eyebrows, eyes, and a mouth with buck teeth.

A world of mysteries on the side, stubbornly refusing to vanish. The paint has bonded with the stone, and they'll whisper the name as long as the building stands.

More next week, because yes, there's more to Minot than that. Much more! Infinite amounts of inscrutable placeness!

As noted, motels. Now if you'll excuse me, I have to write a column. And then troubleshoot the interface for the 2016 Drive-In Theater Intermission site.

It has to be done. No one else seems willing to do it. No, a YouTube channel doesn't count.

|