“Well, here’s a grey, but it’s got some green.” The man at the Sherwin-Williams Store was peering at some swatches. I’d shown him the ASH WHITE sample, and he’d said yes, there’s blue there. After I’d told him there was blue. He was an expert, yes, but when you tell people there’s blue they’re likely to see it.

He took another grey swatch. “That’s muddy. Browns.” Another one. “There’s a yellow there.”

“It would seem,” i said, “that people who want grey are interested in, you know, grey. Without yellow.”

“You’d think,” he said. Daughter was a few feet away, shooting walls of color swatches. Instagram fodder.

He took out another grey swatch with a silly name - Tympanium, or Fluted Column, it doesn’t matter - and I noticed that it changed hue as he took it from the wall, where it was illuminated by a light, into the natural light of the store. Then he put it in a box that simulated natural and artificial light. It was different under each set of photons.

The swatch had assumed four different hues.

Times like this you realize that your perception of the physical world is, shall we say, subjective.

We finally found a grey swatch that behaved like Grey in all possible situations, and I thanked him for his time. On the way out I told Daughter how much the Sherwin-Williams logo unnerved me as a kid. The bucket in space, drenching a world that had fallen over from the weight of paint.

She agreed it was a bit odd, but did not share my remnant unease. We were out on errands together, because she wanted to see if an old iPhone could be turned to her advantage, added to the family plan without much expense. I warned her: Saturday errands are long and arduous. There are six stops today. She didn’t mind. I was happy for the company, and it had been a while since she went along willingly. At some point, you know, they stay behind. One week it’s assumed they’ll come along because they can’t be left in the house alone lest they stick a fork in an outlet, and the next you realize they’re perfectly fine by themselves. Catches you short at first. Then it’s normal.

It’s like the day they leave home for good. Catches you short. Then it’s normal. Different becomes normal. Time sands it all smooth. Fine grit for some things; with others, you feel the bite of the coarse grit.

Third stop was the AT& T store, where we were checked in and informed it would be ten minutes. Off to get coffee at the Starbucks. She had a coffee drink, a Vanilla Lite Latte, her first coffee drink ever. Whether this makes me a bad dad, I have no idea. Her other friends’ parents don’t let them drink coffee. They do let them drink 400 calorie four-buck concoctions, but coffee? Horrors. I went all European on the matter, and decided to mediate her first experience with coffee.

She liked it. She felt very grown-up. And there was the possibility of having her own iPhone, which made her feel even more grown-up. This was a most excellent day.

“This,” I said, holding up my own drink, “is an Americano. Eventually you will come to love coffee for being coffee, not the vehicle for flavors. But this is why I am in good mood when I wake up in the morning.”

“Because you have coffee.”

“No. Because I know that when I finish breakfast, I will enjoy a cup of coffee. It’s the anticipation that gives a lift to life, sometimes more than the thing itself.” We were walking outside, taking one of those shortcuts you know when you’ve been haunting the same mall for three decades, and I wondered how far I should go with this lesson. There’s anticipation, experience, and recollection. The first is effervescent, the second a fugue state, the third a retrospective reordering of reality to make it fit on the shelf where your narrative resides. If you have a narrative, that is.

Some do, and that’s the problem. Some don’t, and that’s the problem.

When you’re young - twenties, let’s say - you have a story. Your story. The more drama you have, the more likely you are to curate your tales, edit your narrative, refine it. You will seek to replay the Highs, and find meaningful tragic resonance in the Lows. You will assign significance to repeating elements, but often the wrong significance - instead of revealing something about your own actions or personality, they signal external truths over which you have no control, and hence have no need to question. You confuse your own story with the way the rest of the world operates. In this mindset, the highs are anomalous and glorious, hopeful signs that things will be different; the lows are grim reassertions of your own personal curse, or something.

If you’re like that, recollection is everything, and it excretes a poisonous glaze over the past. Better to live in a constant state of happy anticipation, pleasant experience punctuated by surprise, and mild happy indulgence towards the things recollected. That’s why I love Mondays: the things to anticipate have been refilled after the weekend’s depletion.

My favorite moment on a trip, I’ll admit, is when we’re back on the ship, and I’m sitting on the balcony with a small cigar thinking about the day and the pictures I took but haven’t seen yet.

Anticipation of experiencing recollection, in other words.

The movie “Magnolia,” which I’ve never seen, apparently has Jason Robards on his deathbed yelling something about regret. It’s the goddamn regret. Well, if you were bad, and suffer the pangs of conscience at the end, I suppose. There are things I regret, and they are specific and detailed. But regret is a useless emotion. It fixes nothing. It’s an apology to yourself, an apologies are easy. There are things I regret not doing, but I had my reasons. I don’t know why I’d spend time regretting anything that wasn’t an unkindness to a loved one you can’t fix.

My mother slapped me, once. I mouthed off. I regret what I said, whatever it was. If she slapped me it means she’d had enough of mouthing off, or attitude, or perhaps whatever distance I had established as part of teenhood. I’ve always thought she was justified in slapping me, because that’s the only emotion attached to the memory. Fixed from the start. I have no idea if she was reacting to something else, to looking for the plump little happy compliant smart boy who had gone away, because she never made the leap to the person I became when I passed into pre-adulthood.

I suspect that may have been the case. There was a point at which I felt as if my new interests were considered beneath me. Comic books, for example. Pop music. This may sound ridiculous, but I not only upset my mother by getting interested in rock, but by listening to Mahler. There was something about Mahler that unnerved her. She heard on some talk show that people who were disturbed found solace in Mahler. It was a sign I was probably doing drugs. Mahler.

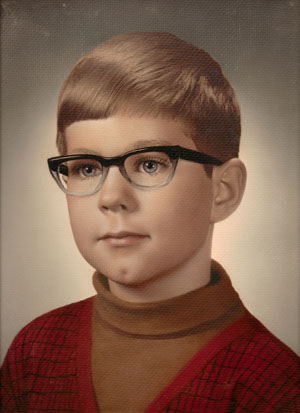

And so I went to college and came back and saw, in my old room, hanging over the bed, this.

The Perfect Me, fixed in time. Thinking about this now makes me realize that every conversation I had when I came back was a performance. I was being who I thought she hoped I would be, a version of Perfect Me extrapolated into capable adulthood.

But I still listened to Mahler.

This would continue for decades, and I don’t think I actually had a real, honest, relaxed, unguarded conversation with my parents until my dad poured me a drink one night and we talked about Things. Never the war, no. But Things.

|