OCHO RIOS, JAMAICA

The little girl was seven, perhaps eight; she had an angel’s face with eyes that were both wary and empty - the former when she looked away. The latter when she looked at you. An unsettling combination. She was dressed in an immaculate schoolgirl uniform. She walked up to the low wall where I was sitting, and asked my name.

She repeated it to herself and wrote it down in a notebook.

I was waiting for the rest of the merry band to come down from the restaurant on the hill. We’d recorded a podcast at an Italian restaurant called Evita’s. Getting there was an interesting exercise in the Jamaican economy. When you got off the dock, you passed the empty bauxite-mine warehouse, passed a shack where officials lounged in the shade, past a hand-made FIRST AID sign that gave no confidence in the dispensary’s stocks, and out to a cheerful Jamaican lady who asked if you needed a cab? No problem. Seven of us said yes. To Evita’s, please. The dispatcher seemed not to know the place but said No Problem. She turned to a driver. Evita’s? The driver nodded and grinned and said No Problem This was a relief, since the reason for going to Evita’s in the first place was to meet with two-dozen Ricochet members from around the country, convening at the behest of the only Ricochet member who lived in Jamaica.

At least he said he was a member; something in the back of my head said we were being lured into an ambush, where we would be relieved of our cameras and recording equipment.

But that’s just silly. C’mon, it’s not like this is Jamaica Jamaica. It’s the part with cops who have sticks and keep the locals from preying on the tourists on their way into town. By the way, where is town? Down there? Very well. We get in the van, and the leader of our group gets the bad news on the fare. It’s preposterous. But who among us could find Evita’s? Who knew how Ocho Rios played out? I was just along for the ride, and since the tab was being picked up by other forces, I just sat in the back, hot and claustrophobic, and steeled myself for a long bouncing ride on the wrong side of the street.

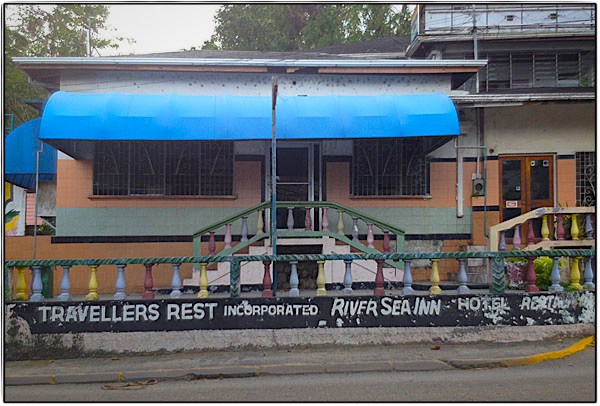

We had to hit a cash machine first. No problem! The driver took us to the tourist area - a two minute drive, tops - where trinkets and hats and shirts and other forms of proof that one had set foot in Jamaica could be procured, and she pointed with pride to a small, tacky replica of the Taj Mahal, erected for no discernible purpose. I doubt there’s a matching shrine to Bob Marley in Bombai. Once we had the money the driver turned a corner - and there was a sign.

EVITA'S 200 YARDS

Walking distance doesn’t begin to describe it. Jumping distance, more like it. A tall man, falling over outside the port, would bump his head on it. But we had paid, and so we went up the hill - the engine of the van straining and complaining - and arrived at a lovely little place with a nice view . . . .

. . . and met the others, already seated and enjoying a mild day in the Caribbean. I had a great talk with our host, who is doing an IB program teaching technology, epistemology, and business to students in Kingston; ordered a promising lunch of spaghetti with jerk sausage, and waited.

I was delighted to see an old word appear on the menu:

Glorified! The word, when I first encountered as a child, had turned into something sarcastic, indicating something of low origin or quality given a superficial improvement that only highlighted its inherent deficiencies. Here it is as it was originally intended: improved in some magnificent way that suggested the blowing of celestial trumpets.

The meal took forever to appear, so we started the podcast without eating, each of us taking turns dashing back to the table to spoon in some food. (Which was amazing. The wall has pictures of the visitors who’ve enjoyed the fare - Anthony Hopkins, Princess Margaret, Keith Richards barely standing, supported by the squat square Evita herself.) When it was done I thought “the ship leaves in an hour. I’d better get going.”

Because I’m bad like that. You never know which complications will be thrown in your way. It was walkable. To hell with throwing money at another cabbie. I joined a knot of fast-walkers and went down the twisting road that lead to the main highway. Lovely place.

A car went past; hard looks from everyone inside. At the bottom of the hill, more people lounging around, giving us a tired glare. As we walked toward the ship vendors came out to sell things - hairbraiding, which could be done if we stopped and went into a dark room off the road; a shell; a bracelet. One vendor, fatally miscalculating his audience, attempted to ingratiate himself with everyone by cheerfully shouting OBAMA! OBAMA! When we passed one lady she complained:

You are not nice people. No one is nice to me today.

I looked down into a resort below, only to find it wasn’t a resort at all.

This wasn’t the utterly destitute poverty I saw in Guatemala in that sad village of tin and cement; there was still something fierce and prideful about that place. This was indolent and exhausted.

Back to the cruise ship dock. I sat down to wait for the rest of the crew. That’s when the little girl approached me.

When she was done writing she carefully tore the piece of paper from her notebook - just a corner, not the page - and handed it to me. It was not my name, as I thought.

Andriana Moncrieff, she said. “That is my name.”

Adriana Moncrieff, she said. “That is my name.”

She sat down next to me. Silent.

I told her it was a beautiful name, and asked her where she lived. She pointed: away. I asked her what she liked to do, what grade she was in, what she liked about school. Her answers were guarded and careful and short.

Finally:

“Do you have any money,” she said. Flat. Rote. Eyes on the gate to see who else might wander in.

I said that I did not. I just had a card.

“A card,” she said.

I showed her my ship ID, and explained that when I gave it to people on the ship, this was as good as money. She held it, turned it around in her hand. A magic thing, perhaps. You give them this and they give you food.

I had, of course, lied. I had cash and I knew it. I sighed and looked up at the great ship in the harbor, deck upon deck of rooms with cool air that came out of the wall with the touch of a button, food summoned by a word on the phone, a bucket of ice in my room every night, hot water for showers, thick towels you could drop on the floor knowing they would be replaced with new ones folded just so. Steak for dinner and lobster if I wished. My world vs hers:

Who sent her out? Who collected her earnings? Who pressed her dress and sent her out to look into the eyes of strangers and make them lie? Who came up with the routine of asking their names, and handing them a piece of paper with her name - something that made you feel as if she had chosen you, claimed you? It was a pretty good idea. It was a damned good idea. A short con that plucked all the right strings.

I got out my wallet and gave her everything I had.

----

Told this story to someone else on the cruise. She shrugged. "Someone in the market tried to sell us a baby," she said. Jamaica.

Back up at the ship I went to get coffee in the only place where you can get a good cup, and had a bitter discussion with a man about how this was the only place where you could get a good cup of coffee. We really bonded on that one. You’ve never seen two strangers who welded their missions in life together with such speed and conviction.

“Last night I just ordered an espresso along with the coffee and I dumped the damn thing in,” he said. “Only way I could drink that swill.”

Sat down with Peter Robinson, who was bemoaning the lack of interesting email he’d gotten. We talked about this and that, and then hello, Victor Davis Hanson appeared; he’d just gotten on board. So we all sat and talked about the new California taxes. I know, I know: such dreary people, but really, when they pass a retroactive tax, announce that your income level and the fact that you have internet access means you probably spent X amount online and were thus now eligible for a bill of X dollars in taxes - which of course you could contest, if you were so inclined - then you have a right to be peeved.

Then the video crew came over. Oh! Right! Gah! Well: last night we did a raucous little podcast, lots of fun, and then retired to the stern for cigars and pizza. Scott, the producer, said we’d do the captain and the tour of the bridge at 3. So I stayed up late reading Tom Wolfe, figured I’d sleep in. The phone had rung at a miserable hour, informing me that the interview with the captain had been moved up to 9:45. Gah! I’d put out the room-service breakfast request for 8:30 - 9:00, and hence I was now stuck here! Waiting! Imitating Tom Wolfe! I said to hell with it, wincing at the thought of the stewards’ reaction when my meal went unconsumed, and headed to the buffet.

On my door handle: the menu I’d set out at 1 AM, an hour before they make the last sweep. Relief. But really, what if I’d counted on this? I should complain.

Upstairs for French Toast.

I’m standing in line, and a little fellow comes over to say hello and offer some nice words about my work here and there. I’m Norman - :::::: I made a mental note: that’s the third Norman I’ve met on this cruise :::: Podhoretz. I have to catch my breath. Well. Wow. We talk about what a sharp and funny fellow his son is, and I thank him for the kind words and the mention in his last book, and how mortified I was to see my name in the index - perhaps something like “and among the most idiotic things said in the wake of 9/11, sure James Lileks’s comment stood alone” or something along those lines.

Ate and dressed in the clothes I’d wear for the video shoots, and went up to the bridge. This is my life and I like it fine:

It's very modern up there, and the wheel is disappointingly tiny. The only piece of classic equipment was an old telegraph - the circular thing with the handle that tells the engine room which speed the captain wants. Still makes that great ringing sound. Just for show, alas. I asked the captain: if the ship was taken over by terrorists who had disabled the bridge controls and this was a movie we could disconnect this and hook it up to the control panels to regain control, right?

His look, such as it was, was priceless. I think he knew I knew it was an utterly idiotic question. I certainly hope so.

No, he didn’t want to talk about the Captain of the Costa Concordia.

When we were done I dressed for Jamaica and off we went to be fleeced by the cab driver. Evita’s / podcast / interview the Senator - walk back.

But now we’re back on the ship, engaged in Petraius speculation, and the camera crew arrives. I had to do a few segments touring the ship. I did? I did. No idea what to say. Think! Think of something to say! Look for a prop! Write it in your head on the run-through, nail it on the first take, perfect it on the safety take, and for GOD’S SAKE come up with something to undercut the whole “welcome to the Love Boat” tone you hear pouring out of your mouth. Which I think I did, since I confessed at the end to stealing 37 small containers of jam from the buffet.

Then: bang. Nap. Out like a light. Dreamed I drove through Jamaica. It was rich and clean and glittered with money and happiness. They had supermarkets with swimming pools in the parking lot.

Woke to the sound of church bells - the phone’s alarm - and remembered that I had a mission. The cigar-and-cognac event would be tonight, and I had to find someone.

We have a spy in our midst. A spy in the house of Buckley. There is a member of our party writing an article on the National Review cruise . . . for the magazine where Tom Wolfe once worked. I flipped open the list of guests and ran my finger looking for someone who was here alone, from New York. Found him. I have a name. Tonight I will seek him out in the throng of the party, cognac in one hand, cigar in the other. I feel like James Bond, but then again: so, perhaps, does he.

Tomorrow: the spy revealed.